Another reason why Christians approach cultural engagement so differently is because of their varying views on common grace and the level of cultural influence, if any, that Christians ought to have. In this third part of the series, I will try to explain how and why Christians can have such different postures toward engaging the world around them. This post is a part of a series that is meant to be read in order. For part 1, start here. For part 2, click here.

In the book Cultural Engagement, edited by Drs. Karen Swallow Prior and Joshua D. Chatrow, Dr. Chatrow tells of a question once posed to him by one of his students. The student’s question went like this:

I have been thinking about Starbucks quite a bit recently. Many Christians support this business and yet their stances on many issues go against my Christian convictions. I don’t see how we can be justified in frequenting their stores. What do you think about this?[1]

How would you respond to this question? Your response might reveal a great deal more about you than you might think. Dr. Chatrow goes on to give several possible responses to the student’s question, which I’ll paraphrase below:

- Every Christian should boycott any companies that have agendas or stances that oppose Christian values. By doing so, we can put pressure on them to change their policies and agendas. We should use strategic activism to directly influence corporations to change their social agenda.

- Out of principle, we should at least try to limit our interaction and cooperation with non-Christian companies. We likely can’t change their position, but at least we can be true to our principles and not be corrupted by secular values.

- We can continue to visit Starbucks so that we can build relationships with the baristas and other patrons in order to evangelize them. Our job is to focus on evangelism rather than externing pressure on business and changing culture.

- We can thank God for the coffee they make – he gave us the means to make this product, and he made the people of Starbucks in his own image with the creativity to make coffee. Besides, Starbucks is creating jobs, and based on universally accepted values, some of their moral intuitions are good.

- We should encourage Christians to open their own coffee shops that lead to human flourishing and that will provide a safe haven from the corrupting pressures of secular society.

Now, I’m not picking on Starbucks here (I frequent them often). You could replace Starbucks with any large corporation, most of whom do not align completely with Christian morals and values. However, this example shows that when it comes to how Christians should interact with the institutions and people around us, what might seem like common sense to you is actually not so common to others.

How should Christians think about interacting with the world around them? One way to answer this question would be to simply list some Scripture passages to try and advocate for a particular position. I have my own convictions, and I could certainly try to convince you of them. Yet I don’t think this would be helpful for at least two reasons.

First, the Bible appears to present a variety of postures toward our broader culture. Simply grouping some Scripture verses together may oversimplify a not so simple question. For example, consider what the Scriptures say about the church and state. The Apostle Paul takes a positive view toward the civil government in Romans 13. But the Apostle John takes a much more negative view in Revelation 19, using the imagery of a “great prostitute” to describe the state.

Consider again two passages from the Old Testament. In Jeremiah 29 we are told to take up residence and seek the good of the city. But in Leviticus 20, God’s people are described as having been distinctly set apart from the nations.[2]

The Bible does not simply give us direct instructions for every cultural context or situation. As Chatrow and Prior explain:

Rather, the Bible includes truth applied to concrete cultural and ecclesial situations of the human author’s context. For this reason, among others, the Bible actually says different things on the appropriate posture toward culture…

The Bible is not contradicting itself with it displays different stances to culture. Instead, it expresses a legitimate diversity – the type of diversity we should relish in and expect, given that God has inspired his Word to guide his people in real-life situations rather than in a theoretical existence abstracted from the messiness of life.[3]

In other words, the Bible does not really give a neat answer to this question. We do a disservice to Scripture when we try to simplify complex issues.

The second reason why I won’t advocate for a particular position here is because earnest Christians have arrived at very different places on this question throughout the history of the church. When we survey some major voices from the Reformed and Evangelical movements (which I will do below), we will discovery a vast array of postures toward engaging the culture.

These differences in postures have been best articulated by H. Richard Niebuhr in his classic book Christ & Culture. For those unfamiliar with his work, I think Tim Keller provides the best summary for Niebuhr’s five positions:

- Christ against culture: a withdrawal model of removing oneself from the culture into the community of the church

- Christ of culture: an accommodationist model that recognizes God at work in the culture and looks for ways to affirm this

- Christ above culture: a synthetic model that advocates supplementing and building on the good in the culture with Christ

- Christ and culture in paradox: a dualistic model that views Christians as citizens of two different realms, one sacred and one secular

- Christ transforming culture: a conversionist model that seeks to transform every part of culture with Christ[4]

It is worth noting immediately that even Niebuhr agreed no person conforms completely to one model.[5]Nevertheless, these models helpfully show that Christians have come to very different answers to our question for their own reasons.

Rather than advocating for a particular position, my purpose in this article is to encourage you to try and understand why you may have the views you do, and why other Christians may have the views they do. If we are going to have any hope of understanding our culture and being faithful witnesses in it, we need to begin by understanding one another. How can we have any hope of being gracious, patient witnesses to those outside the church if we cannot be gracious, patient, and understanding to those inside the church?

There is so much that I could say here, but I’m going to limit the scope of this article to three things: First, two broad spectrums of how Christians have understood common grace, as well as how Christians have understood being an active influence in the culture. After a brief (not brief) analysis of these spectrums, I will give a number of examples from Christian leaders. Finally, I will show a few examples of what our differences might look like within the church today.

Two Spectrums

Every Christian, whether consciously or not, considers a number of factors when they determine how best to interact with their culture. Some of these factors are theological (What are the present effects of sin in the world? What did Christ accomplish? What does he ask of his followers? What is the mission of the church? Etc.), but a number of them are socio-cultural (life experience and events, one’s experience with suffering, family history, ethnic/cultural background, socio-economic class, vocation, education, etc.). Much could be said about each of these factors. Rather than drilling down into any one of them, I want you to see two broad spectrums where every Christian can place themselves.

The first spectrum is our attitude toward common grace, a term which has been given special attention in the Reformed tradition of Christianity. In comparison to God’s special grace, which has to do with matters pertaining to salvation, common grace is extended to all people, both believers and non-believers. God’s common grace is responsible for restraining evil and making life good and just for all people. Common grace accounts for the natural gifts given to all people to work toward a just and beautiful society.

A high view of common grace does not minimize the need for special grace. However, Christians with a high view of common grace will likely have a higher view of the good that non-Christian individuals or institutions can accomplish and might have a lower view toward the present effects of sin in our society. Christians with higher views of common grace are more likely to view secular institutions favorably, to work with them on common causes, and to appreciate truth and beauty no matter where it is found. I also find that Christians with higher views of common grace are more willing to practice historical humility by being honest about the failures of the church in the world.

In contrast, Christians with lower views of common grace will likely have a much lower view of the good that non-Christian individuals or institutions can accomplish. They will likely have a very strong view toward the present effects of sin in our society. As a result, Christians with lower views of common grace are likely to view non-Christian individuals or institutions with suspicion, perhaps even to a point where they advocate for completely withdrawing from working with or among non-Christians.

The second spectrum is our view on the level of cultural influence to which Christians ought to aspire. Christians who believe that Christ calls churches and/or individual Christians to be very influential in the culture will take a very active role in doing so: through politics, the arts, the sciences, and so on. This active work requires the foundation of a Christian worldview, which informs how we distinctly live and act in the world as Christians

Christians who believe that Christ does not call churches and/or individual Christians to be influential in the culture will take a much more passive role. While we each have our various vocations (that are often good and necessary), absent from this end of the spectrum is much talk of the need for a “Christian worldview” or a distinct Christian way of performing our roles in society.

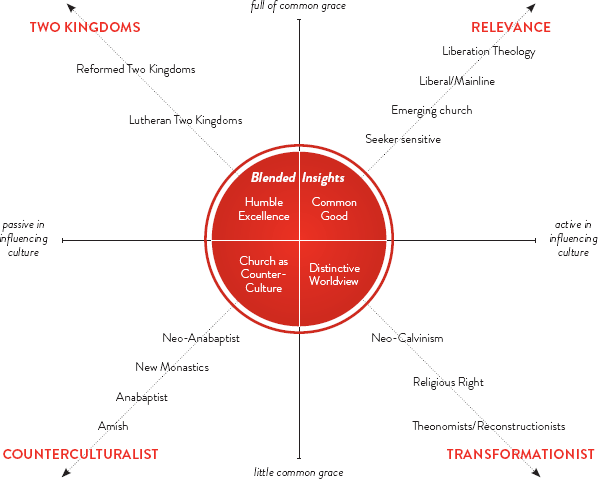

Combining these spectrums can give us a helpful way to understand different postures Christians have toward the culture. The best treatment I have found on the various views that analyzes both the pros and cons of various positions can be found in Part 5 of Tim Keller’s Center Church (or part 3 of this paperback). Toward the end of his analysis, Keller provides this helpful graph:

Notice that our view of common grace (from low to high) is plotted on the y-axis, with our level of influence in the culture (passive to active) plotted on the x-axis. While I have some reservations about how some of the various “camps” are labeled, I find this graph to be very helpful in its broad categorizations as well as the strengths which can be found in each position (more on that later).

Also notice Keller’s “blended insights”; each position has something to offer to the others. We would do well to learn from one another.

Keep in mind that like Niebuhr’s classifications, few Christians will fall in the same place on every issue. However, most of us can likely identify where we most commonly fall. Do you tend to have a low view of common grace, and a low view of Christian influence in the culture? You’re probably most often in the lower-left quadrant. Do you have a high view of common grace and an active stance toward influence culture? You’re probably most often in the top-right quadrant.

In order to give us a clearer picture of what these differences might look like, let’s survey some major Christian leaders from the past and present that would be familiar to a broad Evangelical and Reformed audience. My desire is this next section will give you a greater appreciation for vastly differing views among earnest and faithful Christians.

Examples from Christian Leaders and Theologians

1. Saint Augustine is a major figure in church history, one whom nearly every camp or school of thought will try to claim for themselves. While Augustine would likely not fit into any of our modern categories (he is several centuries removed from our context after all!) we can trace a couple major themes of his views and theology.

First, it is apparent that Augustine had a high view of the knowledge that could be attained of the natural world by those who do not profess Christian faith. In his work on Genesis, Augustine took a hard stance against Christians who say foolish things about the natural world which non-Christians know to be false:

There is knowledge to be had, after all, about the earth, about the sky, about the other elements of this world, about the movements and revolutions or even the magnitude and distances of the constellations, about the predictable eclipses of moon and sun, about the cycles of years and seasons, about the natures of animals, fruits, stones and everything else of this kind. And it frequently happens that even non-Christians will have knowledge of this sort in a way that they can substantiate with scientific arguments or experiments. Now it is quite disgraceful and disastrous, something to be on one’s guard against at all costs, that they should ever hear Christians spouting what they claim our Christian literature has to say on these topics, and talking such nonsense that they can scarcely contain their laughter when they see them to be “toto caelo,” as the saying goes, wide of the mark. And what is so vexing is not that misguided people should be laughed at, as that our authors should be assumed by outsiders to have held such views and, to the great detriment of those about whose salvation we are so concerned, should be written off and consigned to the waste paper basket as so many ignoramuses.[7]

In other words, it is incredibly dangerous for Christians to try and make the Bible say something about the natural world which non-Christians, through their own common grace gifts and talents, known to be false. They will not only view us as “ignoramuses,” but he goes on to say that their hearts will become hardened to the spiritual truths of Jesus Christ and his gospel. Such a strong position comes from a high view of common grace gifts and talents.

When it comes to his views on influence in the culture, there is a range of debate on interpreting Augustine. Those in the Two Kingdoms camp (upper-left quadrant) will be likely to interpret Augustine’s well-known City of God in such a way that would have Augustine argue for a more charitable view of common grace and a higher activity in the culture. Such a reading would say Augustine’s view was such that if we can achieve mutual good with non-Christians, then great. However, these things should not be strived for and we should always recognize that the earthly city will never be like the “City of God” until Christ returns.

However, another reading of City of God would stress Augustine’s view that the earthly city is characterized by the love of self, which leads to all manner of gross sins. This position would argue Augustine’s views lead to monasticism (lower-left quadrant), which believes that the best way to serve God is to separate one’s self from the world.

In either case, it is likely Augustine would fall on the left-most side of the graph, with a relatively passive view of influencing the culture.

2. Like Augustine, John Calvin is another major figure who is claimed by various schools of thought. Once again, we can trace some major themes of his beliefs beginning with his views of common grace. Some would say that it is Calvin who first began to articulate a theology of common grace. As one example, consider this paragraph from the Institutes under the heading of “Science as God’s Gift”:

Whenever we come upon these matters in secular writers, let that admirable light of truth shining in them teach us that the mind of man, though fallen and perverted from its wholeness, is nevertheless clothed and ornamented with God’s excellent gifts. If we regard the Spirit of God as the sole fountain of truth, we shall neither reject the truth itself, nor despise it wherever it shall appear, unless we wish to dishonor the Spirit of God. For by holding the gifts of the Spirit in slight esteem, we condemn and reproach the Spirit himself…But shall we count anything praiseworthy or noble without recognizing at the same time that it comes from God? Let us be ashamed of such ingratitude, into which not even the pagan poets fell, for they confessed that the gods had invented philosophy, laws, and all useful arts.59 Those men whom Scripture [1 Cor. 2:14] calls “natural men” were, indeed, sharp and penetrating in their investigation of inferior things. Let us, accordingly, learn by their example how many gifts the Lord left to human nature even after it was despoiled of its true good.[8]

In sum, truth can be celebrated no matter where it is found as a good gift left to mankind from God.

Calvin’s views on cultural influence are contended, especially among those in the Reformed tradition. Like Augustine, it is doubtful whether he would fit neatly into any modern category. Some will read Calvin through a Two Kingdom (upper-left) lens, citing paragraphs like these:

This, then, is the distinction: that there is one kind of understanding of earthly things; another of heavenly. I call “earthly things” those which do not pertain to God or his Kingdom, to true justice, or to the blessedness of the future life; but which have their significance and relationship with regard to the present life and are, in a sense, confined within its bounds. I call “heavenly things” the pure knowledge of God, the nature of true righteousness, and the mysteries of the Heavenly Kingdom. The first class includes government, household management, all mechanical skills, and the liberal arts. In the second are the knowledge of God and of his will, and the rule by which we conform our lives to it.[9]

Others would point to Calvin’s social reforms in Geneva (education, immigration, care for the poor, etc.) as well as his articulation of justice in order to place him somewhere in the transformationalist quadrant (lower-right). Consider these words from Calvin:

I say that not only they who labor for the defense of the gospel but they who in any way maintain the cause of righteousness suffer persecution for righteousness. Therefore, whether in declaring God’s truth against Satan’s falsehoods or in taking up the protection of the good and the innocent against the wrongs of the wicked, we must undergo the offenses and hatred of the world, which may imperil either our life, our fortunes, or our honor. Let us not grieve or be troubled in thus far devoting our efforts to God, or count ourselves miserable in those matters in which he has with his own lips declared us blessed [Matt. 5:10].[10]

Here, Calvin seems to argue that Christians must be willing to do whatever is necessary in the cause of righteousness to defend “the good and innocent against the wrongs of the wicked.”

In my reading, Calvin is a rare example of a Christian leader who could blend insights from many of our modern categories.

3. Dwight L. Moody was a 20th-century evangelist who models the pietist and Anabaptist views (lower-left quadrant). Moody was reputed to have said:

“I look upon this world as a wrecked vessel. God has given me a lifeboat and said to me, ‘Moody, save all you can.’”

In this view, there is no reason to focus on the physical good or well-being of society. The world is a sinking ship, no matter how many times you scrub its decks it is still going down. Rather than focusing on social activism, Christians are rather encouraged to focus on spiritual matters. Eternal matters are really all that matter.

This pietist school of thought has had a great deal of influence on American evangelism, often leading to a great deal of separation in Christian thinking between “earthly” and “spiritual” issues.

4. Herman Bavinck was a late-19th and early-20th-century Dutch theologian in the Reformed tradition. His work has recently received heightened attention in the Reformed community, for in Bavinck we find an example of a thinker with a brilliant theological mind, a high view of common grace, and a concern for social activism and the concerns of the modern era.

Regarding his views of common grace, Bavinck believed that Christians could view and engage the world generously, celebrating truth and beauty wherever it is found. In The Wonderful Works of God, Bavinck wrote:

“The Christian, who sees everything in light of the Word of God, is anything but narrow in his view. He is generous in heart and mind. He looks over the whole earth and reckons it all his own, because he is Christ’s and Christ is God’s (1 Cor. 3:21-23). He cannot let go his belief that the revelation of God in Christ, to which he owes his life and salvation, has a special character. This belief does not exclude him from the world, but rather puts him in position to trace out the revelation of God in nature and history, and puts the means at his disposal by which he can recognize the true and the good and the beautiful and separate them from the false and sinful alloys of men.”[11]

Bavinck was also very involved in social activism. He was not only active in politics as a Dutch parliamentarian, but he also became increasingly involved in the issues presented in the modern era, like those of war, women’s suffrage, and racism.[12]

In my own interpretation of Bavinck, a Christian who shares Bavinck’s views and concerns will find themselves on the right side of the graph, likely not fitting neatly into either the upper or lower quadrants.

5. So much could be said about the views and ministry of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Those even remotely familiar with Dr. King will instantly recognize him as a leader that viewed Christian cultural engagement and influence as necessary, not optional. His work staging peaceful protests for bus boycotts, voter registration, and sit ins, as well as his regular lobbying of political leaders to accomplish change in the political sphere, reveals a man deeply committed to changing the world for the better. His socio-cultural and political views were built on his Christian beliefs and what he believed the gospel empowered Christians to do in this world:

The gospel at its best deals with the whole man, not only his soul but also his body, not only his spiritual well-being but also his material well-being. A religion that professes a concern for the souls of men and is not equally concerned about the slums that damn them, the economic conditions that strangle them, and the social conditions that cripple them is a spiritually moribund religion.[13]

Indeed, in King’s view Christians must work as though a truly righteous society is actually attainable:

The transformed nonconformists… recognizes that social change will not come overnight, yet he works as though it is an imminent possibility.[14]

But what about his views on common grace? On the one hand, King had a high view of the knowledge and wisdom that could be attained through philosophy, science, and art:

This has led to a widespread belief that there is a conflict between science and religion. But this is not true. There may be a conflict between soft-minded religionists and tough-minded scientists, but not between science and religion. Their respective worlds are different and their methods are dissimilar. Science investigates; religion interprets. Science gives man knowledge that is power; religion gives man wisdom that is control. Science deals mainly with facts; religion deals mainly with values. The two are not rivals. They are complementary. Science keeps religion from sinking into the valley of crippling irrationalism and paralyzing obscurantism. Religion prevents science from falling into the marsh of obsolete materialism and moral nihilism.[15]

On the other hand, Dr. King’s life’s work focused on fighting the reality of sin and depravity in our society no matter where it is found. Such a view is neither overly optimistic about the world, nor overly pessimistic. While many people today would probably try to box Dr. King neatly into the top right quadrant of the graph, I do not think such a characterization is correct or warranted.

6. Moving more into the modern context, 20th-century leaders like Billy Graham and John Stott give us an example of Christian leaders who have tried to reconcile various views and recognize shortcomings of the church in its cultural influence (which is a great example of historical humility as well!). In 1974 these men came together and articulated a more unified vision of evangelism and social activism in the Lausanne Covenant. This vision reflects a more positive view of common grace, as well as a higher level of cultural influence, than was common among Western evangelicals at the time.

Consider this statement from the Lausanne Covenant, which comes from paragraph five (titled “Christian Social Responsibility”):

We affirm that God is both the Creator and the Judge of all men. We therefore should share his concern for justice and reconciliation throughout human society and for the liberation of men and women from every kind of oppression. Because men and women are made in the image of God, every person, regardless of race, religion, colour, culture, class, sex or age, has an intrinsic dignity because of which he or she should be respected and served, not exploited. Here too we express penitence both for our neglect and for having sometimes regarded evangelism and social concern as mutually exclusive. Although reconciliation with other people is not reconciliation with God, nor is social action evangelism, nor is political liberation salvation, nevertheless we affirm that evangelism and socio-political involvement are both part of our Christian duty. For both are necessary expressions of our doctrines of God and Man, our love for our neighbour and our obedience to Jesus Christ. The message of salvation implies also a message of judgment upon every form of alienation, oppression and discrimination, and we should not be afraid to denounce evil and injustice wherever they exist. When people receive Christ they are born again into his kingdom and must seek not only to exhibit but also to spread its righteousness in the midst of an unrighteous world. The salvation we claim should be transforming us in the totality of our personal and social responsibilities. Faith without works is dead.[16]

John Stott’s commentary on this paragraph is worth reading in total. However, for brevity (once again, this series is not at all brief), I will highlight two sections from his commentary. Regarding the statement “we express penitence both for our neglect and having sometimes regarded evangelism and social concern as mutually exclusive,” Stott wrote:

This confession is mildly worded. A large group at Lausanne, concerned to develop a radical Christian discipleship, expressed themselves more strongly, “We must repudiate as demonic the attempt to drive a wedge between evangelism and social action.”

He went on to write:

Justice, reconciliation and freedom—these are more and more the object of human quest in today’s world. But they were God’s will for society long before they became man’s quest. For God loves the good and hates the evil wherever these are found (Psa. 7:9,11; 11:4-7; 33:5). It is written of his King in the Old Testament and applied to the Lord Jesus in the New, “You love righteousness and hate wickedness” (Psa. 45 :7; Heb. 1 :9). The same should be true of us all. “Cease to do evil,” God says, “learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression; defend the fatherless, plead for the widow” (Isa. 1:16,17).

These words from Graham and Stott would likely be regarded as “liberal” among evangelicals today. Yet here they are, articulated by two of the most well-known leaders of the modern evangelical movement. This position would certainly fall on the right side of Keller’s graph. Like Bavinck, Graham and Stott’s positions would likely not fit neatly into the top or bottom quadrants.

7. John MacArthur is a great example from the modern era of a leader who seems to change in his views depending on the circumstance. In general, MacArthur appears to have a low view of common grace, as well as a relatively passive view toward cultural influence.

MacArthur’s views on common grace are largely influenced by his pre-millennial views. For example, in a recent sermon MacArthur articulated his belief that the culture is going to become more and more wicked – and there’s nothing we can do about it:

Oh, guess what? We don’t win down here, we lose. You ready for that? Oh, you were a post-millennialist, you thought we were just going to go waltzing into the kingdom if you took over the world? No, we lose here – get it. It killed Jesus. It killed all the apostles. We’re all going to be persecuted. “If any man come after Me, let him” – what? – “deny himself.” No, we don’t win down here. You ready for that? Just to clear the air, I love this clarity. We don’t win. We lose on this battlefield, but we win on the big one, the eternal one.[17]

Like Dwight Moody, MacArthur’s beliefs have traditionally led him to articulate a more passive role for Christians in regard to cultural influence. In his book Why Government Can’t Save You, he wrote:

If all that is true of you, you will recognize that it is not your primary calling to change your culture, to reform the outward moral behavior and professed political convictions of those around you, or to remake society superficially, according to some kind of “evangelical Christian blueprint.” Instead, you will constantly remember that the Lord has called you to be His witness before the lost and condemned world in which you now live.[18]

Likewise, in an article on the website of MacArthur’s Grace to You ministry, it is explained that MacArthur makes it a point to stay out of politics. Here is one of several reasons given for his position:

Fourth, political involvement can easily confuse the message of the church. Many unbelievers are totally confused by the testimony of the visible church. It’s easy to excuse them for thinking the cause of Christ is about passing conservative legislation or championing social causes. The message of the church is that sinners can be reconciled to a holy God (2 Cor. 5:20-21). God has sent His beloved Son to redeem fallen, broken, condemned, and dying people, to turn His enemies into His friends, to adopt and love ragged, throw-away children and receive them into His kingdom. Political involvement undermines and confuses that clear and winsome message.[19]

To this point, it would appear that MacArthur has a very low view of common grace, and a very passive position on cultural influence. Yet recent actions and statements reveal that MacArthur’s position might not be so clear cut. Given his lawsuit of the state of California for violating religious liberty[20], as well as his public endorsement of Donald Trump for president[21], MacArthur does not seem entirely opposed to political activity. Indeed, MacArthur has been very political in recent sermons, even willing to condemn religious liberty (which is ironic given that this was the basis for his lawsuit against California):

And oh, by the way, I read the other day that one of the evangelical publicists – whatever that is – said he’s happy to let us know that the new administration will uphold religious freedom. Really? The new administration will uphold religious freedom? I don’t even support religious freedom. Religious freedom is what sends people to hell. To say I support religious freedom is to say I support idolatry, it’s to say I support lies, I support hell, I support the kingdom of darkness. You can’t say that. No Christian with half a brain would say, “We support religious freedom.” We support the truth![22]

I believe MacArthur represents a good chunk of evangelicalism today, which has a low view of common grace, and generally has a passive stance toward cultural influence. However, when the need arises to defend their rights, MacArthur and those like him will get very politically involved – and fast.

8. Dr. James Dobson is well-known for his work with the Focus on the Family institution. While much of his early work focused on teaching Christians how to live in a secular and sinful world (left side of the graph), in recent years Dr. Dobson’s work has become increasingly more involved in cultural and political engagement. In fact, Dr. Dobson stepped down from his role at Focus on the Family in 2003 to protect their tax-exempt status while he became more involved in politics.

Since that time, Dr. Dobson has clearly aligned himself with the Religious Right (not that this was ever in doubt), using his influence to endorse candidates such as John Thune of South Dakota in 2004 (in order to defeat Tom Daschle), or his recent endorsement Donald Trump for president. In Dobson’s view, unless Christians stand up and get involved in politics, America will become “fundamentally transformed” by what as he perceives as sinful liberalism. Thus, in an October 2020 letter to supporters he wrote:

If you love America and don’t want it to be “fundamentally transformed,” it is time to do three things:

- Pray like never before that God will spare this great nation from tyranny and oppression of religious liberty.

- Volunteer to help your candidates.

- Vote for the candidates who will best uphold your values and convictions.

Also, consider forwarding this letter to your friends, family, and others whom you might influence.[23]

Like many in the Religious Right, Dobson’s views reflect a low view of common grace and the secular state. Those who view the culture as Dobson does will be inclined to oppose what they view as increasingly sinful world, often through direct political action.

9. Dr. Russell Moore of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC) for the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) has been the subject of much praise and consternation since he became their president in 2013. The SBC is the world’s largest Protestant denomination and has often been closely associated with the Religious Right and the Republican party. However, under Dr. Moore’s leadership the ERLC has attempted to cut ties with any one political party and has instead advocated for a unique Christian witness in the culture.

Without going into specifics on Dr. Moore’s positions, it is clear from his work that he advocates for a unique, highly engaged Christian voice in the culture. Several excerpts from his 2015 book Onward make this point. For example:

Our call is to an engaged alienation, a Christianity that preserves the distinctiveness of our gospel while not retreating from our callings as neighbors, and friends, and citizens.[24]

He continues later in the book:

In fact, the call to a gospel-focused engagement is a call to a more vigorous presence in public life, because it seeks to ground such witness where it ought to be – in the larger mission of the church.[25]

While Dr. Moore advocates for a highly active public Christian witness, he rejects the idea of being too closely tied with one particular religious party. Such attachment will end up requiring us to abandon gospel convictions for the sake of party success:

It would be a tragedy to get the right president, the right Congress, and the wrong Christ. That’s a very bad trade-off. The gospel makes us strange, but the gospel doesn’t make us actually crazy.[26]

In addition, we will ally ourselves too closely with those who share our angers and frustrations, rather than aligning ourselves with those who agree with us on the gospel:

We have adopted allies on the basis of this intensity of outrage rather than on the basis of consistency with the gospel. If you are angry with the same people we are, you must be one of us. Jesus just never operated this way. The Pharisees were at odds with the Sadducees; Jesus angered them both. The zealots were at odds with the tax collectors; Jesus redeemed them both. His ministry wasn’t, first of all, anti-Pharisee or anti-Sadducee, anti-zealot or anti-collaborator. His mission was the kingdom of God, and that casts judgment on every rival reign.[27]

Such views have made Dr. Moore the subject of constant criticism. To the secular world, his views on abortion make him intolerably conservative. To the world of the Religious Right, his views on immigration or religious freedom make him a dangerous liberal.

10. Dr. Stephen Um is a pastor in the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) and a council member of The Gospel Coalition (TGC). Dr. Um would be representative of a modern Neo-Calvinist (lower right) position, which has a hopeful but honest view of common grace and is moderately engaged within the culture. A Neo-Calvinist will view social activism as being “secondary” but necessarily attached to the proclamation of the gospel. As a result, many Neo-Calvinists are distinctly orthodox in the Reformed and Evangelical beliefs but are also more committed on issues of justice and mercy than many of their Two Kingdom (upper left) brothers and sisters might be (I recognize this is a generalization that does not always fit).

In his commentary on Micah, Dr. Um explains his views on biblical justice which would reflect the position and level of engagement that would define many in the Neo-Calvinist camp. He writes:

When we think of doing justice, we typically think of something like performing retribution. Most people equate justice with punishing wrongs. That’s certainly part of what justice entails, but it’s actually much broader than that. It is certainly giving the perpetrators their due, but doing justice is also giving those who cannot stand up for themselves—the victims, the poor, the powerless, the vulnerable, the voiceless—their due as well. It is more than only punishing wrong; it is creating a situation and a society where everything is right—a society where every last person in it, including the most vulnerable and the weakest, can flourish and thrive. That’s what doing justice, according to the Bible, really means.[28]

It’s loving so deeply, so fully and stubbornly, that we refuse to budge until everyone, including the most vulnerable of society, can flourish and thrive. That is the nature of justice.[29]

If you go back and read Calvin’s position on justice, you should fairly easily be able to see the connection between Calvin’s beliefs and the statement Dr. Um makes here.

11. The & Campaign is a recent coalition formed with the mission of educating and organizing Christians for civic and cultural engagement that results in better representation, more just and compassionate policies and a healthier political culture.[30] Their position is that a biblical worldview requires Christians to be involved in social and political issues, striving for both redemptive justice and values-based policy. The & Campaign believes that Christian political engagement has often one or both of these qualities.

In 2020, leaders from the & Campaign, including Justin Giboney, Michael Wear, and Chris Butler published a book which articulated their beliefs at length concerning what Christian political engagement ought to look like. Through cultural and political engagement, Christians can love both God and neighbor:

Whether we’re protecting the unborn, supporting fair prison sentences, or making sure the elderly are taken care of, politics provides a forum for advocating for our neighbor’s well-being and pursuing justice. Our daily walk should be a promotion of the love and truth of the gospel. Treating all God’s children with human dignity through the political arena is an opportunity we should not bypass…

…Accordingly, we should participate in politics primarily to help others and to represent our Lord and Savior in the public square.[31]

Like Dr. Moore, the positions of the & Campaign cannot fit neatly into a “liberal” or “conservative” party. The & Campaign strives for an honest but hopeful view of common grace, as well as a highly active role in cultural influence.

These 11 examples are an incomplete but broad picture of the varying views within the Reformed and Evangelical traditions today. While I’m sure readers will find themselves naturally gravitating toward certain leaders over others, my hope is that you have a better appreciation for the varying views among earnest Christians today.

Let’s try and put this all together by considering a few examples of what these differences among Christians might look like today.

Putting it All Together

By now, I hope the Starbucks example at the beginning of this article makes much more sense to you. While you may not share any concern over drinking Starbucks coffee, you ought to have a better appreciation of why there are so many positions among Christians today concerning how to engage “secular” companies like Starbucks.

Let’s consider a few other examples of how Christians approach a range of issues today.

- Politics

Many Christians are at odds with one another over how to engage in politics. Is political engagement even necessary? If so, what should it look like? Must Christians align themselves with a particular party? Is there only one way true Christians can vote?

There are no easy answers to these questions. Some, believing the world to be a wicked place and that sinfulness must be opposed at all costs will not only be more involved in politics, but will also be much more likely to align themselves with a particular party or group. Many who hold this view will feel quite strongly that there is only one way genuine Christians can vote (their way, of course).

Others, believing that it’s not the Christian mission to be attached to politics or seek cultural reform, will take a much more passive stance toward politics – often to the infuriation of the first group.

It can be a real conundrum to Christians in either of these groups when they realize that for the most part, they’re all in agreement on core matters of theology and ethics. Nevertheless, how those views work themselves out in varying levels of cultural engagement and political influence couldn’t be more different.

I hope you can see how earnest Christians might come to these differences in view while still being in agreement on core matters of the faith. The demonization of those who disagree with us politically – even among Christians – should have no place in our churches.

- Abortion

More specifically, let’s think about abortion for a moment. What does it mean to be pro-life? There are many answers to that question. Some Christians might view that term primarily through a political lens, thus advocating for political involvement that might restrict abortion access or even appeal Roe v. Wade.

Other Christians, perhaps in agreement with the first group on a low view of common grace, might instead advocate for the institution of Christian-led pregnancy and women’s centers to provide an alternative for women considering an abortion.

Still others, disagreeing with either of these two groups, will want to work within existing systems, such as adoption and foster care agencies, with the hope that a focus on adoption presents a more robust pro-life witness to the world.

Of course, on the issue of abortion many Christians are able to work together with others who hold differing views in order to achieve the common goal of saving as many children as possible. Nevertheless, there are great disagreements as well. Is an abortion-ending political stance necessary to vote for a particular political candidate? Can a Christian still be considered pro-life if they vote for a pro-choice candidate (often for the sake of promoting what they view is a more robust pro-life position)?

If we could turn down the volume and stop shouting at one another, we might find that we agree on more than we think. Are we willing to try and understand our differences in order to work toward our common pro-life goals? I hope this grid could provide one tool toward that end.

- CRT

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is the latest in a long line of evangelical boogeymen. According to some Christians, CRT is the most vile and wicked idea and the greatest threat to the church today. According to other Christians, the entire issue is largely a distraction from fighting racial injustice, and CRT is just another secular theory that will come and go.

One’s disposition to CRT will largely be consistent with one’s general view of common grace. If you have a low view of common grace, you will likely be much more inclined toward being skeptical of any idea, theory, or political position which isn’t derived from a distinctly Christian perspective. In addition, a lower view of cultural engagement might make one feel that talking about “cultural” issues is irrelevant. Christians ought to “stick to the gospel.” Such a position will likely lead us to being dismissive of something like CRT since it is largely advocated by secular thinkers and leaders. According to many in this first group, CRT should not even be discussed among Christians other than to reject it entirely. To even entertain a conversation about it is a threat to the Church.

If you have a higher view of common grace, you will likely have a much more neutral, even generous starting point toward different ideas, theories, or positions – regardless of if they’re not coming from a distinctly Christian worldview. In addition, higher views of common grace and cultural engagement will lead us to desire dialogue and mutual understanding with those who hold different views from us. Rather than starting from a skeptical and dismissive posture toward CRT, Christians in this second group might be much more willing to look for common ground, perhaps even willing to learn a thing or two if there is any truth to be found in something like CRT.

The first group will look at the second group as being compromisers who threaten the Church. The second group will look at the first as being too critical and uncharitable. Both will view the other as compromising gospel witness.

Once again, if we could simply take the time to understand one another, we might find that we have more in common than we think. While we may disagree in methods, Christians in either group would find that we’re all committed to the peace and purity of the church, ending racial injustice, and having a genuine gospel witness to non-Christians. Our differences likely have much more to do with our views on common grace and cultural engagement than they do core theological beliefs.

Final Thoughts

Similar examples could be given from the arts, the sciences, philosophy, and so on. My hope is that this article has given a couple tools to those with a heart for cultural engagement and genuine Christian unity. We will engage culture at our best when we are able to engage one another at our best. This requires the ability to understand one another and find common ground.

In a recent journal article, Dr. Gray Sutanto articulates a summary of Herman Bavinck’s position on having a Christian Worldview. At the end of the article, Dr. Sutanto provides three ways Christians can learn from Bavinck. The second point is relevant to our topic here. Dr. Sutanto writes:

Secondly, Bavinck’s Worldview thinking deepens understanding, rather than simplifies. Worldview thinking in our day often times simplifies thinkers by categorizing them together under an “ism” and then dismissing them. We might be tempted, for example, to say that we need not deal with Derrida and Foucault because they were advocates of “postmodernism”, or we say that Kant and Hume were all proponents of “modernism.” Such a move simplifies rather than deepens, because we reduce them into a simple caricature – a worldview – in order to dispense with them, not noticing the insights, details and complexities that these thinkers uniquely pose. In other words, he opted for patient description rather than facile denunciations.

Bavinck pushes us to explore particular thinkers deeply and to seek to find out their first principles, that which is behind what they are saying, their foundations and assumptions. He treated each thinker with the appropriate care required before he adjudicates on their worldview. We do well, then, to emulate this desire to treat each thinker with patience and care, rather than boxing them into an “ism” that we can dismiss beforehand.[32]

In other words, Christians ought to engage seriously with those who hold different views from their own. If this is true for how Christians engage non-Christians, how much more so ought it to be true of how Christians engage other Christians?

I suggest that if we have any hope of seeing a Church with winsome cultural engagement, it needs to start in our local churches. At the very least, this ought to mean that our churches should be a safe space for discussing differing views on even the most difficult topics. While every local church will likely have a corporate identity that gravitates toward one particular position, no one with a differing position ought to feel censored or muzzled. True Christian unity will be achieved not when we agree with one another on everything, but when we fully understand and commit to one another, even in our disagreements.

—

[1] Cultural Engagement, Edited by Joshua D. Chatrow and Karen Swallow Prior, 32.

[2] These examples are taken from Cultural Engagement, Chatrow and Prior, 34-36

[3] Ibid., 37

[4] Timothy Keller, Center Church: Doing Balanced, Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City ,194.

[5] Niebuhr: “When one returns from the hypothetical scheme to the rich complexity of individual events, it is evident at once that no person or group ever conforms completely to a type.” Christ & Culture, 43-44.

[6] Timothy Keller, Center Church: Doing Balanced, Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City , 231.

[7] Augustine, Works of Saint Augustine, trans. Edmund Hill, vol. 13, On Genesis: On Genesis: a Refutation of the Manichees, Unfinished Literal Commentary On Genesis, the Literal Meaning of Genesis,186-87

[8] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 2.2.15.

[9] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 2.2.13.

[10] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 3.8.7.

[11] Herman Bavinck, The Wonderful Works of God, 21.

[12] For more, consider this summary of James Eglington’s biography on Bavinck here: https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2021/january-web-only/herman-bavinck-critical-biography-james-eglinton.html

[13] Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Strength to Love, 159.

[14] Ibid., 18.

[15] Ibid., 4.

[16] https://www.lausanne.org/content/covenant/lausanne-covenant

[17] https://www.gty.org/library/sermons-library/GTY178/2020-clarity-reflecting-on-gods-goodness-in-the-last-year

[18] John MacArthur, Why Government Can’t Save You, 145.

[19] https://www.gty.org/library/questions/QA207/why-does-john-avoid-political-issues-and-politics

[20] https://religionnews.com/2020/08/13/john-macarthur-grace-community-church-lawsuit-worship-protest-gavin-newsom-eric-garcetti/

[21] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrIeEBN3fOM

[22] https://www.gty.org/library/sermons-library/GTY178/2020-clarity-reflecting-on-gods-goodness-in-the-last-year

[23] https://www.drjamesdobson.org/newsletters/october-newsletter-2020

[24] Dr. Russell Moore, Onward, 8.

[25] Ibid., 29.

[26] Ibid., 31.

[27] Ibid., 36

[28] Stephen Um, Micah for You, 118.

[29] Ibid., 119.

[30] https://www.andcampaign.org/about

[31] Justin Giboney, Michael Wear, and Chris Butler, Compassion & Conviction, 11 & 17.

[32] https://journal.rts.edu/article/bavincks-christian-worldview-context-classical-contours-and-significance/