An old meme has been circulating again. The caption reads:

An old meme has been circulating again. The caption reads:

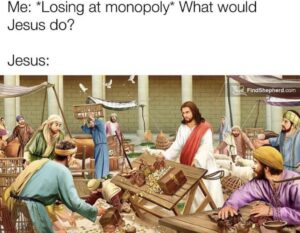

Me: *Losing at Monopoly* What would Jesus do?

Jesus:

Underneath the caption is a picture of Jesus flipping the tables in the temple, a familiar scene to many people as it is not only found in all four of the New Testament gospels, but it is the most vivid picture of Jesus’ anger that we have from his earthly ministry. The meme adds levity to a weighty historical account, even if it wildly distorts the source and reason of Jesus’ anger.

As readers, we tend to be more familiar with a compassionate, gentle, patient Jesus. A Jesus who flips tables, shouts, and drives people out of a temple with a whip he made with his own hands; well, that can be shocking, discordant, and disturbing.

Why exactly was Jesus so angry? An overlooked detail in the story might reveal to us that Jesus’ heart was not only inflamed for pure worship and justice, but that his anger also came from a deeply personal place. Such an interpretation of this account would give instruction to us on how we relate to the poor and the oppressed, as well as how we take sides for justice in our communities.

Three Guilty Parties

While the general events of this scene are familiar to most, it is important to keep in mind that this operation in the temple courts was massive. This is no weekend farmer’s market that Jesus was disrupting. In one account, the first-century historian Josephus noted that over 255,000 lambs were slain in the temple on Passover! This would not include the other animals – doves, pigeons, etc. – that were sold and slain as well. Jesus is making a scene in an absolutely massive event. Mark’s account of this story demonstrates the culpability of three parties who are involved in the temple incident in brief fashion.

Here is his account:

On reaching Jerusalem, Jesus entered the temple courts and began driving out those who were buying and selling there. He overturned the tables of the money changers and the benches of those selling doves, 16 and would not allow anyone to carry merchandise through the temple courts. 17 And as he taught them, he said, “Is it not written: ‘My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations’? But you have made it ‘a den of robbers.’”

18 The chief priests and the teachers of the law heard this and began looking for a way to kill him, for they feared him, because the whole crowd was amazed at his teaching. (Mark 11:15-18)

The first group which contributed to the offense were the money changers who exchanged currencies in the Temple. The money changers would have exchanged any number of foreign currencies into the Tyrian shekel, the closest available currency (of pure metal, and with no graven images) that could be used for the temple offerings laid out in Exodus 30:13-16.

The second group were the sellers of animal sacrifices, specifically, in Mark’s gospel, are those who sold doves and pigeons. These birds were the provision for poorer worshipers who could not afford a lamb for sacrifice (Lev. 12:6-8).

In themselves, neither act is notably offensive. The proper currency and sacrifice were required for worship in the temple. However, it is the proximity and intention of the sale which creates the offense and leads to Jesus’ anger. What should have been a mere means for individuals to acquire sacrifices had instead turning into a bazaar for people to turn a profit. Worship became a commodity, and the Gentiles first experience in the temple of the God of Israel would have been no different from any of the pagan Gods.

Jesus’ heart toward this end is evident in his citation of Isaiah 56:7: Is it not written, “My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations?” Jesus is zealous for God’s worship to be pure and free from any trappings which would prevent those who are far from God from experiencing his grace and salvation.

Often, this zeal for pure worship is where our teaching and interpretation of this passage typically ends. However, there are additional layers we need to consider here. This market system also exploited the poor. We see this in a few ways in this passage. The citation from Isaiah 56:7 is in the broader context that prohibits evildoing. The call of Isaiah 56 is both to “maintain justice and do what is right” as well as “keep the Sabbath without desecrating it.” (Isaiah 56:1-2). In God’s economy, injustice and idolatry are almost always connected.

Furthermore, in both Mark 12:38-44 and Luke 20:45-21:4, Jesus accused the temple authorities of being thieves who preyed on the poor and elderly. In Mark’s account of the temple incident, it is those who sold doves and pigeons to the poor who are targeted by Jesus’ anger.

What we see, then, is that the markup on currency exchange, and the selling of sacrifices to the poor, had created an exploitative and unjust system that preyed upon those of humble means. The temple authorities had failed to heed the prophet’s words in Jeremiah 7 – they had exploited the poor and the widow (Jer. 7:5-9; cf. Jer. 5:28) and thus came under the condemnation of Jer. 7:11. They were now a den of thieves.

Which leads to the third guilty party – the priests themselves. This entire operation came under the watch and blessing of the priests, and thus they had incurred the Lord’s judgment for this injustice. John Calvin vividly captured the guilt of the priests when he wrote:

And Christ inveighed against [this practice] the more sharply, because it was well known that this custom had been introduced by the avarice of the priests for the sake of dishonest gain. For as one who enters a market well-stocked with various kinds of merchandise, though he does not intend to make a purchase, yet, in consequence of being attracted by what he sees, changes his mind, so the priests spread nets in order to obtain offerings, that they might trick every person out of some gain. (Calvin, Commentary on the Harmonization of the Evangelists, Matthew 21:12, emphasis mine).

Injustice is hated by our God. When it is done by those who claim to be his people, it is a deep offense that will not be tolerated. Those who bless systems of injustice while claiming the name of God will receive the harshest punishment: “I will thrust you from my presence” (Jer. 7:15). Jesus’ righteous anger and clearing of the temple is a picture of the judgment of God on an unjust people. He will not stand for it.

Getting Personal

So, purity of worship and unjust exploitation are certainly on the table (pun intended) as drivers of Jesus’ anger. However, if we pay close enough attention, we might notice a detail that suggests Jesus’ anger had another source. The exploitation in the temple, and the barrier to God’s mercy that was subsequently created, was deeply personal for Jesus.

Note that both Mark and Matthew’s accounts target the table of those selling pigeons and doves who are subjects of Jesus’ anger. It is not those selling animals in general who were targeted, but those who sold animals to the poor.

Who do we know in the gospels who had to buy doves and pigeons instead of the preferred lamb?

Mary and Joseph (Luke 2:24), Jesus’ own parents.

Jesus wasn’t just angry at exploitation of the poor in general (though, as bearer of the Divine heart, he is). Jesus saw in the faces of those being exploited his own family: his mother, his aunties, his neighbors. In his incarnation, Jesus has taken solidarity with the poor, the oppressed, those of humble means and origins. He has taken to himself a family of whom the world looked down upon. In so doing, he demonstrated that God’s heart is to side with the oppressed against oppressors (Ps. 146:7); with the humble against the proud (Luke 1:52).

When you miss with the poor, you mess with Jesus himself.

It should not surprise us, then, when Jesus said that whatever we do for the least of these we do for him (Matthew 25:40). Jesus’ earthly life demonstrated a deep relational solidarity with the poor and the oppressed. Jesus did not expressed anger at oppression in general, nor did he sit back and point fingers at how everyone else needed to change. Jesus actually entered into deep solidarity with the poor. He took their side. He called them mother, friend.

Injustice wasn’t just an idea. It was personal for Jesus, and he would not stand for it.

Charity is More Than We Think

There is an instruction here for us. The question for us is not simply, “Does your heart break at injustice?” – though it should. However, this question alone conveys injustice as an impersonal and intangible force.

A better question for us might instead be, “Does your heart break over the injustice your family and friends experience?” Is injustice personal for you? Are you in relationship with the poor and marginalized in your community?

It’s not enough to saw we’re against exploitation. It’s not enough to stop at book clubs and social media statements – though those things may be good and useful. Indeed, it isn’t enough even for us to give generously of our financial resources so that things might change.

Jesus’ ethic calls for something deeper. Do our lives evidence solidarity and relationship with the poor and the oppressed? Or do our lives, our good works, still convey a certain distance and unwillingness to get closer to those who are looked down upon in society? Charity without relationship is merely transactional. Jesus wants more from us.

In a powerful address in the Netherlands on November 9, 1891, the Dutch theologian and politician Abraham Kuyper challenged the church to take up the call to address poverty and injustice in society. What made Kuyper’s words so relevant then, and perhaps even now, is that Kuyper called the Church to respond to poverty and injustice in uniquely Christian ways. Kuyper believed that the Christian response to poverty and injustice was unique from secular movements. Part of that distinctiveness came in his belief that Christian discipleship ought to shape our entire lives around seeing and addressing poverty and unjust systems. In one pointed section of this speech, he said:

I hasten to add that a charity which knows only how to give money is not yet Christian love. You will be free of guilt only when you also give your time, your energy, and your resourcefulness to help end such abuses for good, and when you allow nothing that lies hidden in the storehouse of your Christian religion to remain unused against the cancer that is destroying the vitality of our society in such alarming ways. For, indeed, the material need is appalling; the oppression is great. You do not honor God’s Word if, in these circumstances, you ever forget how the Christ (just as the prophets before him and the apostles after him) invariably took sides against those who were powerful and living in luxury, and for the suffering and oppressed. (Kuyper, The Problem of Poverty, 62).

Do our lives look anything like this? Do we even believe this?

Jesus’ earthly life communicates the heart of God. His stance against injustice was not merely theoretical, it was deeply personal. A uniquely Christian social ethic demands deep relationship and solidarity with the poor, marginalized, and oppressed in our communities. When we take their side not just in word, or even in our deeds, but in relational solidarity, only then can we say we are beginning to love like Jesus loves and hate what he hates.