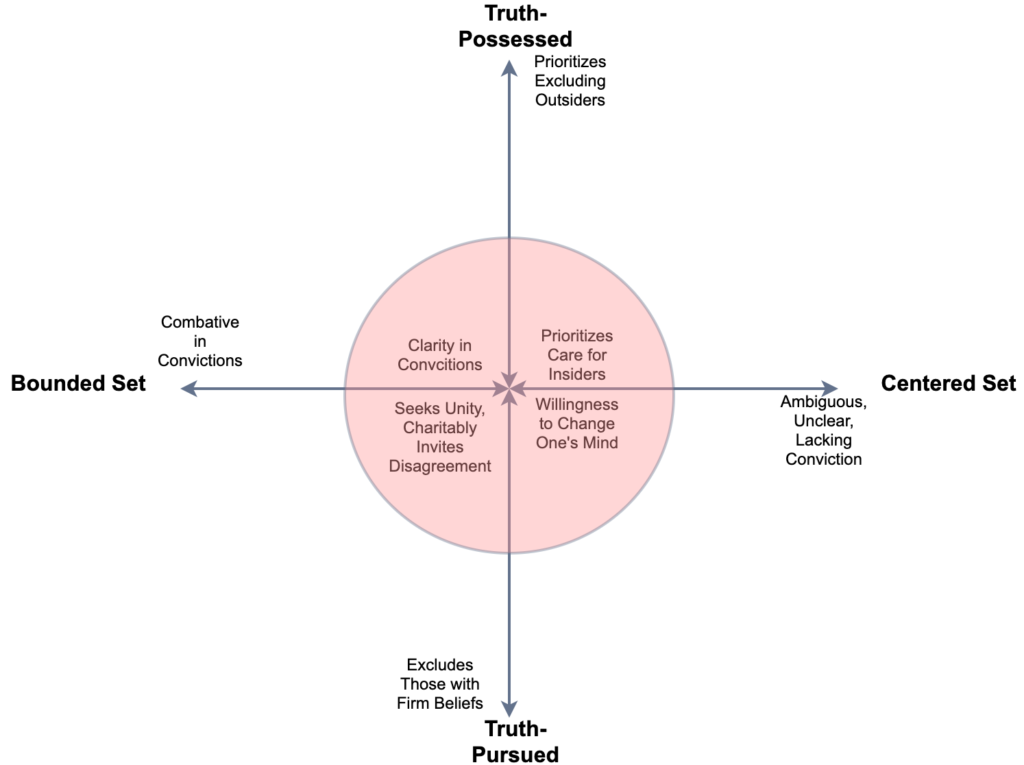

In the previous post I endeavored to put forth a useful framework to describe how a healthy Christian disciple holds their beliefs. This framework was the result of bringing together two paradigms which initially contrasted opposing ideas.

The first paradigm contrasted bounded set beliefs with centered set beliefs. Bounded beliefs are those which place firm boundaries on who is “in” or “out” of any given community; be it a community of faith, politics, or some other shared values. Centered beliefs place less emphasis on boundaries and are more concerned about the direction an individual is headed in. You may not need to agree with us on everything, but if you like the idea of where we’re going then you’re welcome to come along.

The second paradigm contrasted a posture of being truth-possessed with a posture of truth-pursued. To be truth-possessed is believe to some degree that you possess the total truth and that you have the right to determine who has access to that truth. Someone who has a truth-pursued posture might believe that truth is out there, but it is always something to strive for, that can never be totally attained.

Rather than setting each of these four ways of believing against each other, I instead set each on their own spectrum ranging from health to unhealth; from the strengths of each posture to its weaknesses. My argument was that each of these four attitudes can inform what it means to be a healthy Christian disciple. Rather than setting firm beliefs against loose beliefs, we are closer to what Jesus asks of us if we discover how to hold firm convictions with kindness, charitability, and a willingness to admit we still have much room to grow.

The result of this argument was the chart you see pictured here, which is larger in the previous post. I concluded my argument with this summary of a healthy Christian disciple:

I concluded my argument with this summary of a healthy Christian disciple:

When we put these paradigms together, we get a picture of what Christians look like when they hold their convictions with charity and kindness. A healthy posture of belief holds clear convictions about orthodox doctrine (John 17:17, Acts 2:42, 1 Corinthians 15:2) while acknowledging that our perspective is limited and fallen (1 Corinthians 13:12) and needs to be constantly informed by the knowledge and perspective of others (Proverbs 27:17, Ephesians 4:15). Healthy Christian communities prioritize care for insiders (Galatians 6:10), never to exclude outsiders (Colossians 4:5-6), but to demonstrate and live into the love of Christ to the world (John 17:23). Kind, Christlike disciples emphasize agreement and unity wherever possible (Mark 9:38-41, Philippians 1:15-18).

This encompassing framework is the foundation for the point I’m really trying to make in this series, which is this: Confessionally Reformed Christians (those who hold to the Westminster Confession of Faith) have great reason to be those who demonstrate convictions with kindness and charitability.[1] While I originally intended to write one more post to make this point, in order to do this subject justice (and be kind to readers!), I’ll be building this argument over the next four posts in the coming weeks.

I do not expect all my readers to be confessional (hold to the Westminster Confession), or even know what the Westminster Confession is.[2] I do hope this series is attractive to those who may want to pursue the Westminster Confession further. For those who already consider themselves confessional, my aim for this series is that it will be an encouragement to you to see how our shared convictions ought to fuel kind, happy, charitable Christianity.

While I do not plan to spend much time on this final point, an implicit “between the lines” argument is that those Christians who say they are confessional but demonstrate patterns of rudeness, unkindness, ungraciousness, or even maliciousness, are not demonstrating confessional belief at all. Instead, they have bought into the idols of power-brokering and culture-warring that are all too common in this present age.

My current plan is for this series to take up at least four more posts. We will consider the history of the Westminster Confession, as well as its substance, and evaluate how it ought to shape us into kind, charitable, convicted Christians. Over the next two posts, I want to demonstrate how confessionalism in its essence makes us both bounded and centered in our beliefs. That is, confessional Christians are those who both hold firm convictions and are willing to explore ideas with which they find disagreement. The Confession principally does this by anchoring us to orthodox belief, which abates our fears and disciplines us toward trust.

Fear of the Other

Joshua 22 is a salient story in Scripture for us to study and apply in this cultural moment. Two-and-a-half tribes (the Reubenites, Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh) had made a deal with Moses (Numbers 32) and confirmed with Joshua (Joshua 1:12-18) that they could settle on the east side of the Jordan River. After Joshua gave permission for these tribes to go and settle on the east side of the river, news came back to the people of Israel that these two-and-a-half tribes had made an alternative altar for worship (Joshua 22:10-11). In fear, the people of Israel assumed that these other tribes were worshipping false gods at this altar and prepared to go to war against them (22:12).

Fortunately, the people of Israel decided to send an envoy to issues charges of idolatry before coming to blows (22:13-20). Of course, rather than issuing charges, the people of Israel ought to have first listened to the two-and-a-half tribes, but fear makes us do silly things. In their response, these other tribes reveal their true motivation: fear (22:21-29). These tribes feared that in the next generation, the children of Israel would say to their children that on account of the distance between them, the children of these two-and-a-half tribes have no share in the blessings of the Lord (22:24-26). Hearing this response, the envoy of Israel is satisfied to allow the altar to remain, and civil war is averted (22:30).

This story reveals to us the importance of bounded beliefs in how they address our fears of others and shape us in being trust-giving, charitable Christians.

At this point in redemptive history, the people of Israel had a set of bonded beliefs. The law had been given through Moses, and this is now the first generation who has entered the promised land with God’s Word in hand. On the surface, then, this account might suggest that bounded beliefs are really no help at all. If the people of Israel had God’s Word, had seen his miraculous presence, had received the promise of the land – then why such fear?

Given how new all of this was for the Israelites, it would be appropriate for us to show them some grace and patience. We could say that while the Israelites had bounded beliefs in principle, in practice they were completely unbounded in what it looked like to hold their beliefs. The Word they had received which ought to have governed their civic, religious, and domestic lives had not yet been tested and applied through all of life’s uncertainties and complexities.

So, when a potential threat from within their community showed itself, what was their response? Fear. They had not yet been conditioned by the shared bond of the law to trust each other, and instead gave into their baser instincts of fear and conflict.

Confessionalism Builds Trust

Confessional Christians, however, are in quite a different place in redemptive history. God’s Word has stood for millennia. It has been tested age after age, and no argument, evidence, or cultural moment has been sufficient to destroy its credibility. Most importantly, Jesus Christ has come! The Word has been made flesh, and for nearly two thousand years he has shown himself to be faithful to build his church. His people have learned to trust him and apply his Word age after age, and we stand on the collective faithfulness and wisdom of saints who have gone before.

This faithfulness has been passed on to us to a great degree in the Westminster Confession. Finalized in 1646, the Westminster Confession of Faith has stood for nearly four centuries as a faithful expression of what the Bible teaches on key issues of the Christian faith. It has been applied in the global context, in several cultures, across multiple eras. This document still stands as one that is more than sufficient to unite believers in shared convictions and faith.

If this is true, then there is no room for fear and distrust among Confessional believers. Unlike the early Israelites, we have a tested and applied set of bounded beliefs. If I agree the Confession communicates essential Christian truth, and if you agree that the Confession is your interpretive grid for Scripture just as it is for me, then my fundamental disposition toward you must be one of trust. If I instead adopt a posture of reactive fearfulness and distrust toward my confessional brothers and sisters, I am saying something significant about the Confession: that it is inadequate, insufficient, and unable to create the bonds of fellowship that it is intended to create.

Yet this degree of trust ought not to benefit confessional believers alone. In his work on the family, Abraham Kuyper argued that the family is the incubating community which teaches us to trust other human beings. The trust we learn show to our spouses, our parents, and our children then overflows to the state. In other words, healthy families produce healthy citizens; distrust in a society reveals a breakdown in the family.[3]

This relationship between the family and the state is analogous to relationships confessional Christians hold in the public sphere. The confessional community is an incubator where Christians learn to trust and believe the best in other believers. The Confession is a tool which shapes me into a trusting, charitable, believing-all-things, hoping-all-things, enduring-all-things kind of Christian (1 Cor. 13:7). As I learn to trust and be charitable toward my confessional brothers and sisters, I learn to become more trusting and charitable with those who are outside my particular Christian tradition, even with those who may be hostile to my faith.

My fundamental disposition toward other confessional believers must be one of trust. My disposition toward all image bearers must be to believe the best in them. When I react toward others with fear and distrust, then I am revealing how ineffective the Confession is for me in practice.

If the Confession is doing what it is intended for in my own life, then when I hear or read something from a confessional believer which might make me suspicious, I will first seek understanding and believe the best in them. I will not react maliciously on Twitter. I won’t be snarky, sarcastic, or drag their name through the mud. I won’t join siloed groups whose purpose it is to slander other believers. I won’t talk about my brothers and sisters in private Facebook groups, text threads, or email chains. [4]

No, if the Jesus is using the Confession as a sanctifying tool in my life, then I will believe and hope for the best in my brothers and sisters, even when I don’t understand, even when they say or do something that might initially raise some alarms for me. This trust I show toward my confessional brothers and sisters will overflow to how I treat all Christians, indeed it will overflow into the love I show toward all those who are made in God’s image.

In this way, we see how bounded beliefs (like the Westminster Confession), at their best, also cause us to be centered in our willingness to walk alongside others with whom we have disagreement. I may not agree with you on everything, but I trust you and I like the direction you’re headed, so I’m willing to tag along.

In the next post I’ll address how confessionalism not only deals with the fears we have of others, but also the fear we have for ourselves. The Confession is an anchor which keeps us rooted in the Scriptures. Therefore, we need not fear new or different ideas. Instead, we can with confidence explore new ideas, taking the best from them, while knowing that our confessional faith will keep us rooted in Christ and his Word. Such a posture makes us kind and charitable in our discourse with all people, always seeking to represent other positions in their best light, always desiring to learn where we still have room to grow.

[1] I am not suggesting that Confessionally Reformed Christians are better in any way that Christians of other traditions. I am arguing that this tradition ought to produce exceptionally kind, charitable, convicted believers; not that other traditions could not do the same.

[2] Nor do I expect my audience to all agree on what it means to be confessional; it is not my intention to wade into the debates of “Good Faith” subscription or “Strict” subscription. Wise readers will recognize that I hold the former, but I am including the latter here in agreement with what it means to be “confessional.”

[3] See, “The Family, Society, and the State” in On Charity and Justice, especially pages 280—282.

[4] At the risk of addressing a significant issue that can’t be resolved here, it must be said that at some point some people reveal themselves to be untrustworthy. Wisdom and patience are needed here. When other believers reveal a pattern of behavior that is not in good faith, that might even be dangerous, then they have lost the right to trust. If someone has repeatedly maligned our character, they are not worthy of our trust. Again – wisdom, patience, and even grace, is needed here.